cars

I led a team that built really efficient cars

During my undergrad at Duke, I was a part of Duke Electric Vehicles, a club that built electric vehicles to push the frontier of fuel efficiency. We were a completely student-led team of 15 undergrads. Our team competed in the Shell Eco-Marathon, where 100 teams annually compete to carry a driver a fixed distance using the smallest amount of fuel. These vehicles stretch the definition of a “car”, and often only have three wheels are are just big enough to fit a small driver lying down. They have a limited top speed and no suspension. However, they push the absolute extreme of what is possible to build. While normal passenger cars often get 20-40 miles per gallon (MPG), these vehicles often get efficiencies above 1000 MPG.

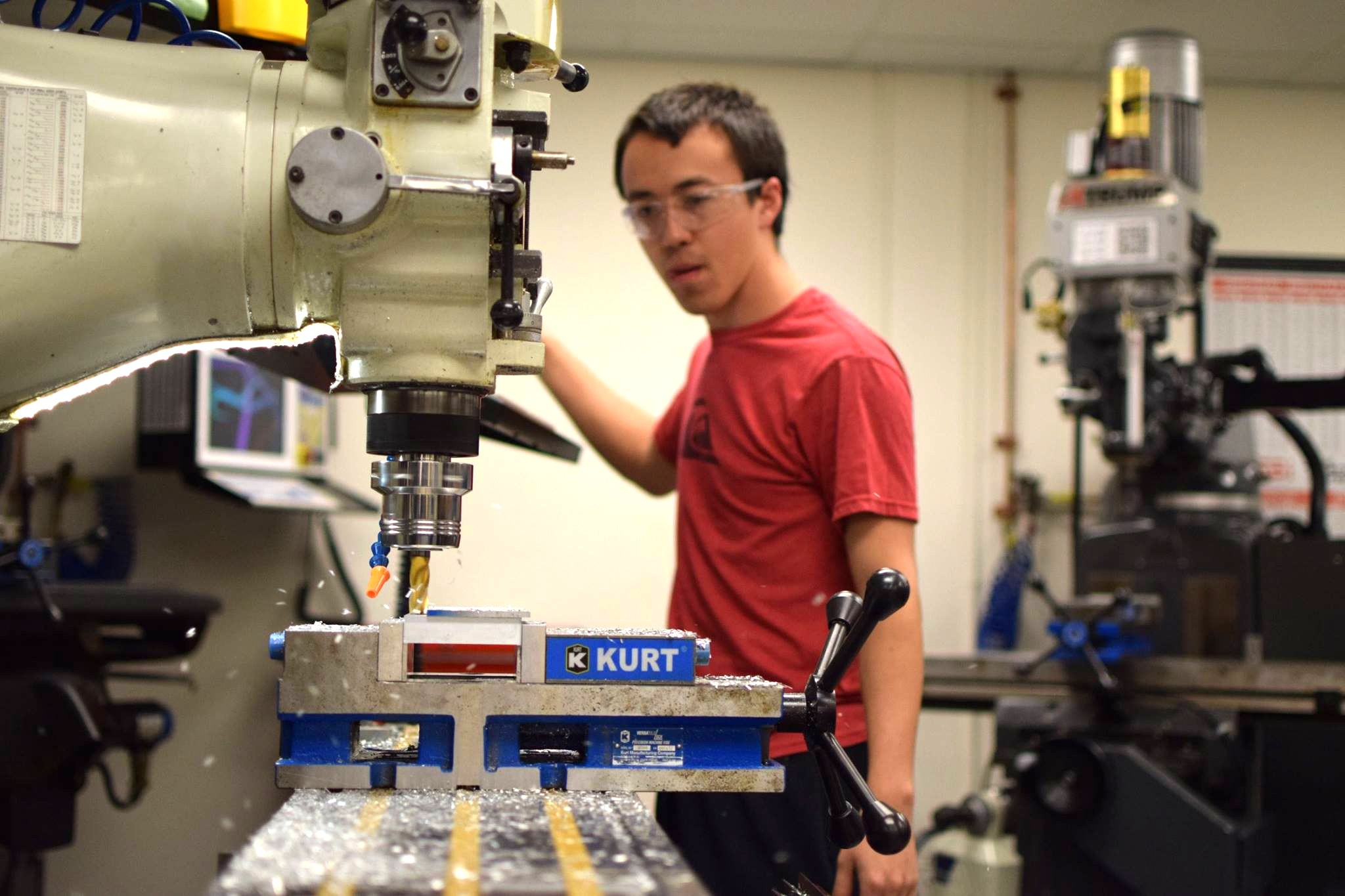

I joined the team during my first year at Duke. I worked on the vehicle’s motor controller. This is a piece of power electronics that switches the DC from the battery to 3-phase AC for the vehicle’s motor. Power electronics often blow up when things go wrong, which makes development an interesting process. During my third year, I was promoted to become the president of the team, where I took charge of the overall design of the car, management of the finances, and leadership of the team.

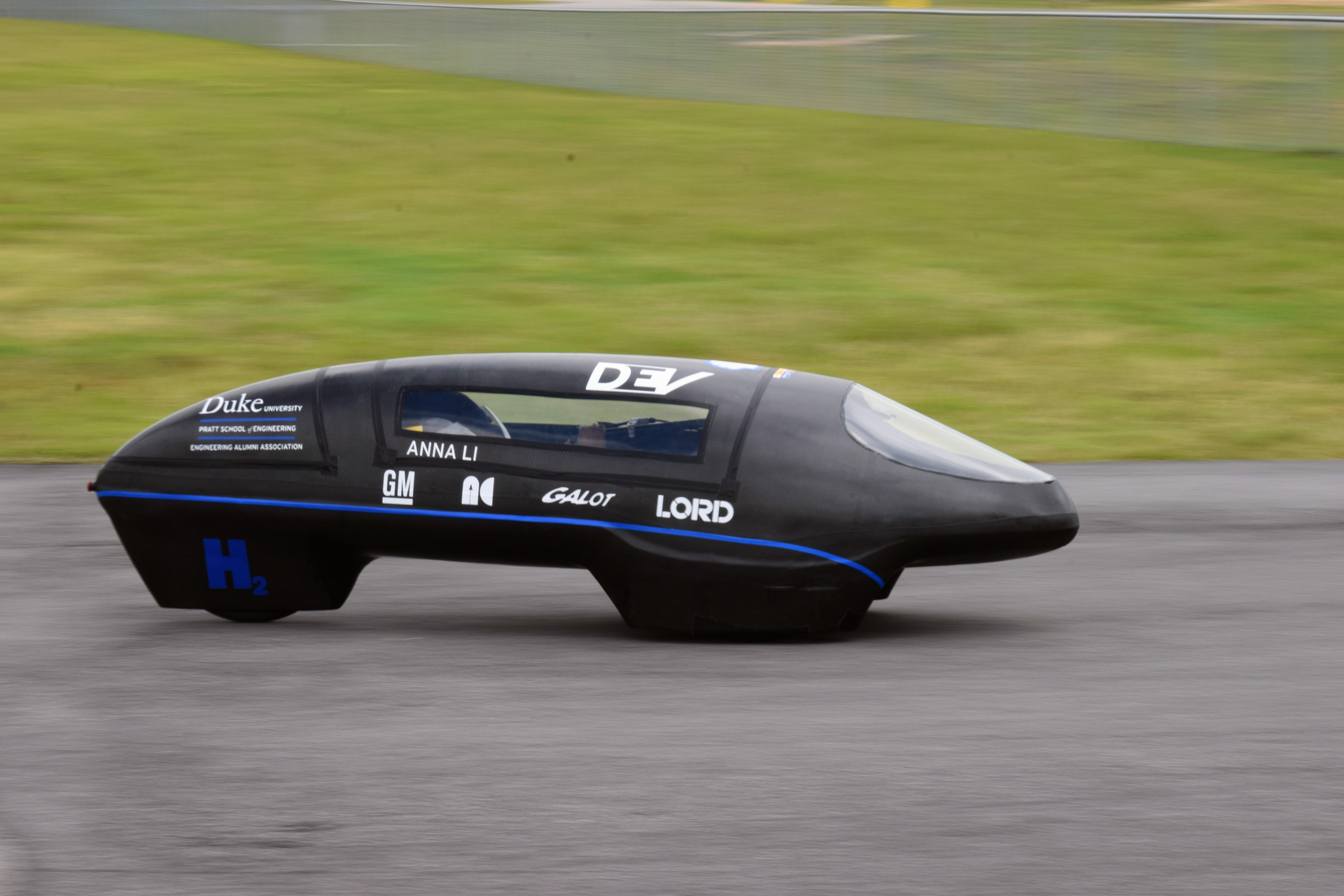

As the new president in my third year, we got a blank slate when designing our next car, Maxwell. I led a push to increase the vehicle’s efficiency to a new level. The vehicle’s shape was optimized using CFD to reduce drag, and the weight was minimized using stress simulations. We developed techniques to build the car more precisely to minimize tolerances. The resulting product was sufficient to win the 2017 Shell Eco-Marathon, where our team placed first in the electric vehicle category.

In my last year at Duke, we focused on building the team’s first hydrogen-powered vehicle. While we had zero experience with hydrogen fuel cells, we dove headfirst into figuring it out. Due to the efficiency of the vehicles, the power requirement from the fuel cell was fairly low, <100 watts, making development easier. We also designed and built an active hybrid system, where the fuel cell would charge a supercapacitor bank which powered the motor. This hybrid system allowed the fuel cell to continously operate in its most efficient range while the power demanded by the motor could fluctuate. Our innovations in the hydrogen-powered car were sufficient to win the 2018 Eco-Marathon in both the hydrogen-powered and electric-powered categories, in addition to a technical innovation award.

While I had graduated at this point, based on the performance we had seen at the end of the year, we thought that breaking a world record might be possible. The previous world record was held by PAC-CAR II from ETH Zurich in Switzerland. Their team built a hydrogen-powered vehicle at an efficiency of 12,600 MPGe. A few other students and I decided to stick around campus for the summer to see what we could do. We decided to make Maxwell our world record contender, and modified it to use a hydrogen fuel cell.

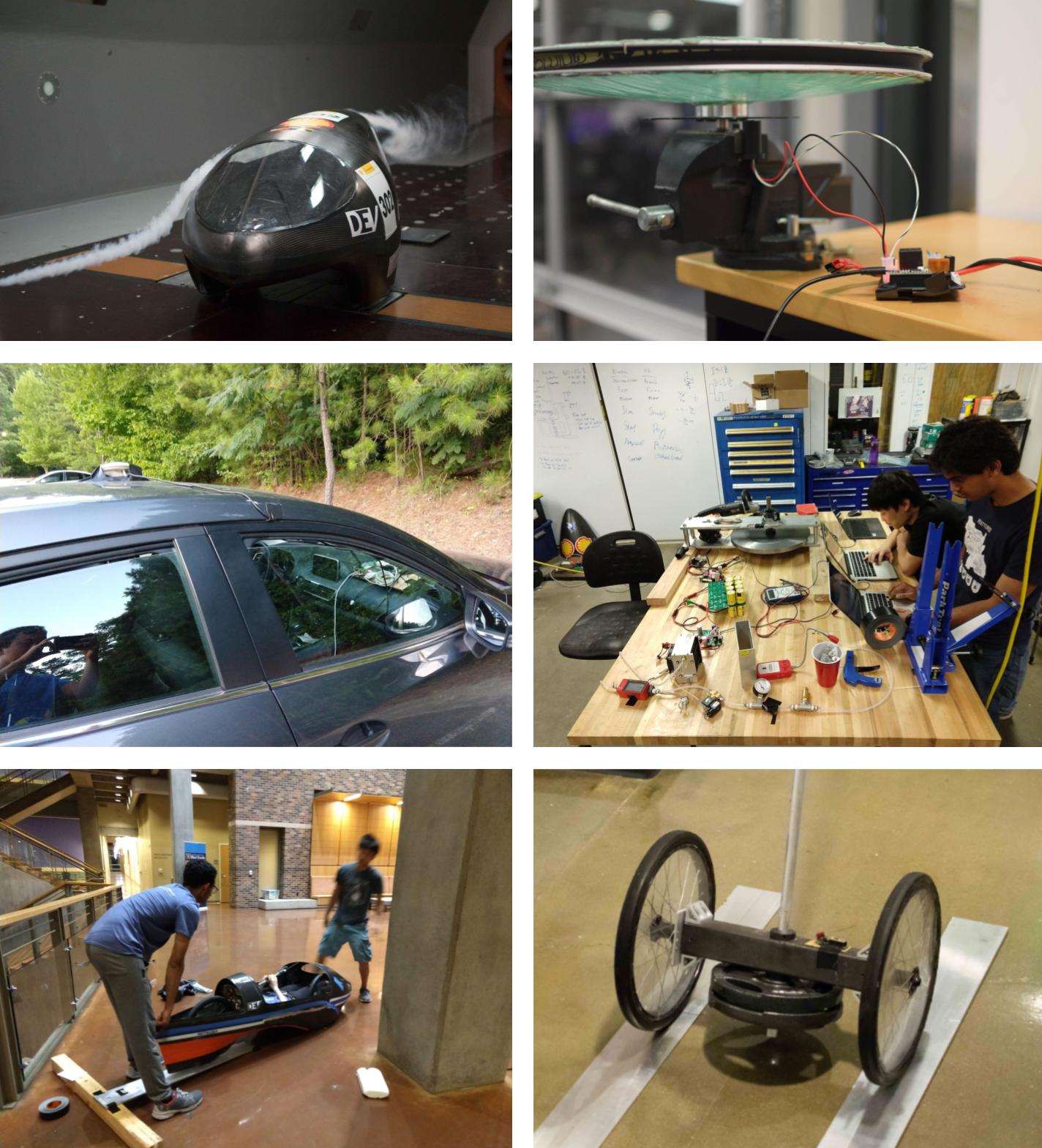

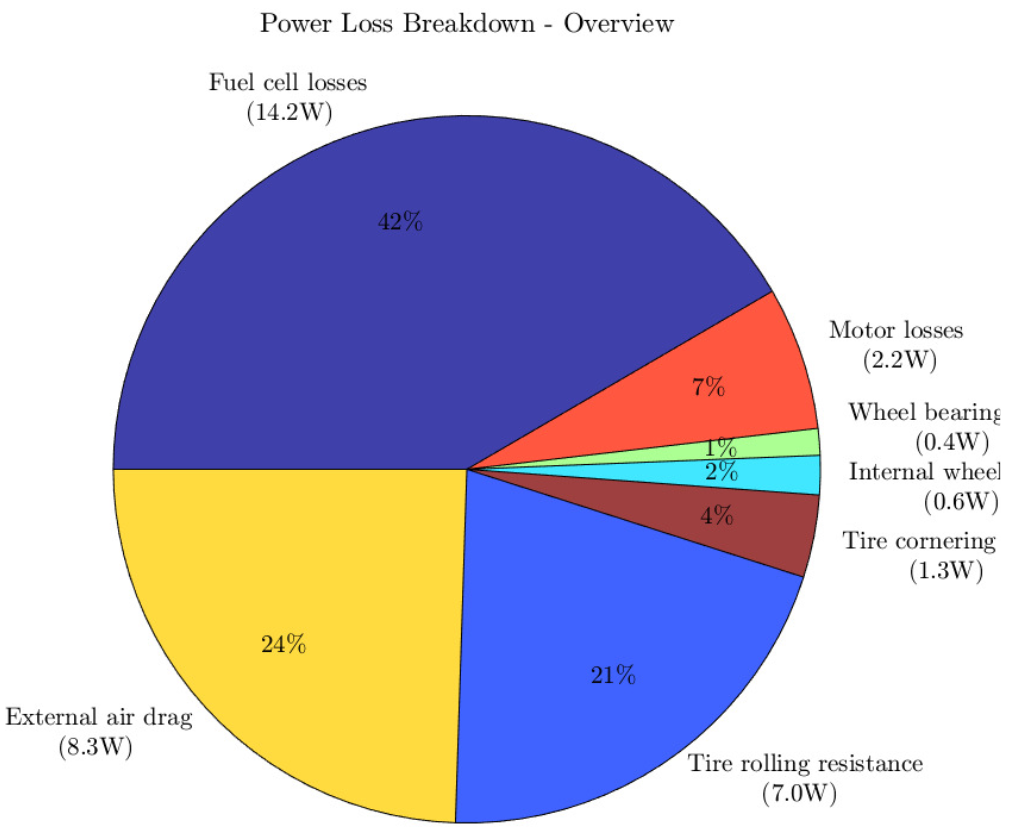

Over the summer of 2018, I led a major push to quantify the energy losses in the vehicle. It’s obvious that there are various sources of drag, such as air resistance, motor losses, and wheel bearing drag. However, what is the significance of each one? What should we as a team invest effort into improving? How close is our real-world implementation to the theoretical efficiency stated on the datasheets? These are all critical questions, and if we were to break a world record, we needed to understand exactly where each Joule of energy went.

We decided to attack this problem by building testing rigs to measure each part of the vehicle in isolation, then perform real-world track tests. Ideally, we could make the bottom-up efficiency estimate and top-down on-track performance match closely. By having setups to measure each component’s performance on the bench, we could also get much more repeatable measurements. For example, we found that the aerodynamic drag from the wheel spokes spinning inside the car was 150 milliwatts. An unacceptable amount!

Our testing effort allowed us to build an accurate model of vehicle performance, shown below. These results were published in VPPC 2019. Understanding the main sources of energy losses allowed us to focus our efforts on improving the most important parts of the vehicle.

As our team worked on the car, we incrementally improved it’s performance. In particular, significant gains were achieved in managing the fuel cell to operate in it’s most efficient range and modifying the tires to minimize rolling resistance. We also developed analysis framework to understand when the car performed worse than our model.

Our first world record attempt occured on July 14th, 2018. We attempted the record three times, but due to a variety of technical problems, the car didn’t complete the course during the first two attempts due to an overheating fuel cell and issues with the motor controller. On the final attempt, one of the vehicle’s tires leaked, resulting in a score 20% lower than prior attempts.

For the next week, our team worked on ironing out bugs in the car for a second attempt. On July 21st, 2018 we had our second attempt on a cloudy, cool morning. We broke the record on our first attempt, but kept on pushing to increase efficiency even further. Our next two attempts pushed the record higher and higher. In our final attempt, our vehicle covered 13.629 km at an average speed of 24.29 kph using only 0.6016 grams of hydrogen. Our overall efficiency was 14,573 MPGe, setting a new world record!

Description of second world record in progress…